Lumbar spondylolisthesis is the most common location for vertebral slippage to occur. Of all the lumbar spinal conditions we cover, spondylolisthesis is one of the most important, since research evidence exists linking many cases of this atypical structural issue to the existence of lumbar back pain and various forms of neurological dysfunction. This fact sets it apart from many other diagnoses that are often assumed to be pathological, when no proof of a pain-inducing mechanism exists.

Spondylolisthesis comes in many severities and is usually a relatively benign change in normal spinal anatomy. However, listhesis can always worsen with time and activity, making all cases potential causes of painful symptoms at some point in life. Luckily, patients with severe expressions represent the extreme exceptions to the rule of asymptomatic nature or minor symptomatic activity.

This patient guide offers important details for anyone who has been told they demonstrate listhesis in the lumbar spine. We will examine the severity grading system of spondylolisthesis, the causes of vertebral migration and the usual symptoms that might be expected from each variety of condition.

Grading Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

Vertebral migration is classified according to the percentage of total slippage demonstrated by the affected vertebra in relation to its neighbors. The vertebral body provides an accurate reference point for this measurement and allows doctors to grade spondylolisthesis according to the following 4 categories:

Grade 1 spondylolisthesis describes minor changes in vertebral body proximity where the total movement of the bone is less than 25% displacement.

Grade 2 spondylolisthesis describes moderate changes in vertebral body proximity where the total movement of the bone falls in the range of 26% and 50% displacement.

Grade 3 spondylolisthesis describes severe changes in vertebral body proximity where the total movement of the bone falls in the range of 51% and 75% displacement.

Grade 4 spondylolisthesis describes extreme changes in vertebral body proximity where the total movement of the bone falls in the range of 76% to more than 100% displacement.

Most cases of spondylolisthesis are grade 1 or 2. Only a small percentage of patients demonstrate the worst degrees of vertebral slippage.

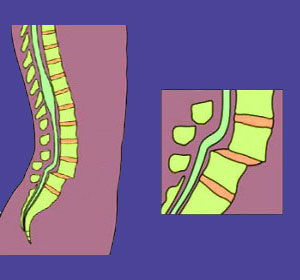

Additionally, vertebral bones can move forward in the spinal anatomy towards the anterior of the body. This is called anterolisthesis. They can also move rearwards in the spinal anatomy, relative to their neighboring vertebrae, towards the dorsal surface of the body. This is called retrolisthesis. When the term listhesis or spondylolisthesis is used without additional reference, it is presumed that the condition is one of anterolisthesis, since this is more common.

Causes of Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis is impossible to demonstrate given a normal spinal anatomy. This is because the vertebral bones link to one another and can not migrate forward or backwards to any significant or permanent degree. Spondylolisthesis is usually preceded by a fracture or congenital defect in the pars interarticularis. This section of the vertebral bone resides between the traverse process and the articular process. If this section of bone is damaged, the vertebra might be allowed to migrate forward or rearward out of alignment with the remainder of the spinal bones.

Why would the pars interarticularis become damaged? In many people, there is a congenital defect wherein the pars is thinner and weaker than in a typical spinal anatomy. In others, there is already a hole or lack of closure of the pars as a congenital condition. However, not all pars defects are congenital.

Injury to the spine can cause the pars interarticularis to fracture, freeing the vertebra for possible migration. The force of the trauma might also help to displace the vertebra significantly, possibly creating a high grade listhesis condition acutely.

Finally, severe spinal aging, bone porosity and certain other conditions can dispose the pars interarticularis towards fracture and subsequent vertebral slippage. This is why lumbar spondylolisthesis is often seen in elderly people, despite their being no history of traumatic injury to the lower spine.

Symptoms of Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

Most minor to moderate cases of listhesis do not create symptoms. Even some cases of grade 3 and 4 spondylolisthesis can be completely asymptomatic. However, even grade 1 cases are linked to lower back pain in some patients, so all cases should be carefully evaluated as potential sources of lumbar dorsalgia and sciatica.

When lower back pain symptoms are present, they are usually caused by impingement of nerves, either in the central vertebral canal (more likely in grade 3 or 4 listhesis) or in the neural foramen (likely with any grade of listhesis). Symptoms will mirror any other types of compressive neuropathy, with the patient suffering a transition of expressions beginning with pain and evolving towards numbness, weakness and dysfunction in the buttocks, legs or feet.

Pain might also be created through mechanical interactions, since the spinal joints are no longer properly aligned and the vertebrae do not move against one another in a natural manner. This is usually the explanation for localized pain, even when nerve compression is absent. Many patients demonstrate one type of pain or the other, while some will display both neurological compression, as well as mechanically-motivated discomfort.

You can learn everything there is to know about spondylolisthesis on our web resource Spondylolisthesis-Pain.Com.

Lower Back Pain > Causes of Lower Back Pain > Lumbar Spondylolisthesis